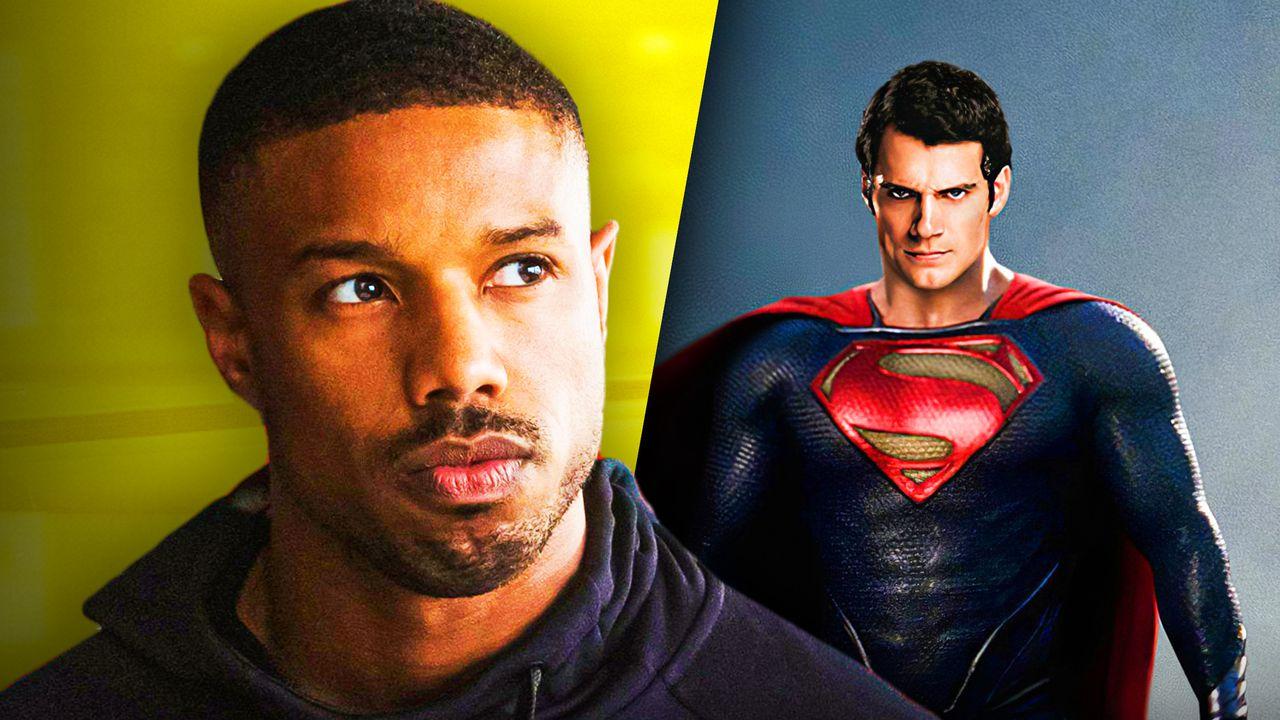

Occasionally, reports surface of a Black actor being cast as Superman—and the internet predictably erupts. Twitter wars rage, comment sections become battlefields, and everyone picks a side. But buried beneath this familiar cultural skirmish lies a fascinating example of a rhetorical maneuver that shapes far more of our discourse than we realize.

The Controversy, Dissected

When casting news breaks, criticism typically follows a predictable pattern. Fans express discomfort with the choice, often framing their objections around "faithfulness to the source material" or "respecting the character's established identity." They argue that Superman, as conceived, represents a specific archetype—the all-American farmboy from Kansas, complete with the mental image most readers have carried for decades.

This isn't necessarily about race, they insist. It's about cognitive consistency. For many fans, Superman is the square-jawed, blue-eyed farm boy they've internalized through countless comics, movies, and TV shows. Changing that feels jarring, like replacing the Coca-Cola logo with Comic Sans—technically possible, but it disrupts deeply embedded expectations.

The Immediate Counter-Attack

But here's where things get interesting rhetorically. Rather than engaging with the casting argument on its own terms, critics of the criticism immediately shift the conversation to moral terrain: "He's an alien from another planet—why would he need to be white? You're just being racist."

This is a textbook example of what rhetoricians call "shifting grounds"—relocating a discussion from one domain (casting choices, character interpretation, audience psychology) to another (racial prejudice, moral failing, social justice). Instead of debating whether established character imagery matters in adaptations, we're suddenly debating whether someone is a racist.

The move is rhetorically powerful because it transforms the original critic from someone with a creative opinion into someone defending themselves against accusations of bigotry. The conversation dies, replaced by moral posturing and defensive explanations.

The Counter-Evidence Problem

But here's what makes this ground-shift particularly problematic: it doesn't hold up against observable evidence.

If resistance to Black Superman casting were primarily driven by racism, we'd expect to see consistent patterns of rejection toward Black characters in comic book properties. Yet the opposite is true. Miles Morales—the half-Black, half-Latino Spider-Man—has achieved massive popularity and critical acclaim. Fans embraced him enthusiastically, despite him "replacing" Peter Parker in certain storylines.

Consider other beloved Black characters who've gained significant followings: Lucius Fox became a fan favorite in Christopher Nolan's Batman trilogy. John Diggle emerged as one of the most popular characters in the Arrow TV series, despite being created specifically for the show. Mr. Terrific has maintained a dedicated fanbase across multiple comic book runs.

If comic book fans were simply racist, these characters would face constant rejection and marginalization. Instead, they've found genuine appreciation and support from the same communities that express skepticism about Black Superman casting.

What's Really Happening?

The real issue appears to be cognitive, not racial. Superman carries extraordinary cultural weight—he's arguably the most iconic superhero ever created, with a visual identity that's remained remarkably consistent for over 80 years. When people object to changing that imagery, they're often responding to the disruption of a deeply embedded mental model, not expressing racial animus.

This is fundamentally different from creating new Black characters or race-swapping less iconic figures. Miles Morales succeeded partly because he wasn't trying to be Peter Parker—he was allowed to be his own character with his own story. The cognitive dissonance wasn't there because fans weren't being asked to overwrite existing mental models.

The Rhetorical Trap

By immediately shifting grounds from "character interpretation and audience psychology" to "racial prejudice," defenders of diverse casting create a rhetorical trap that actually impedes meaningful conversation about representation. Instead of exploring nuanced questions about adaptation, cultural iconography, and audience psychology, we get stuck in endless cycles of accusation and defense.

This pattern extends far beyond superhero casting. Watch for it in political discussions ("That policy seems flawed" → "You just hate poor people"), workplace dynamics ("This approach isn't working" → "You're not being collaborative"), or social media debates ("I disagree with this approach" → "You're part of the problem").

Breaking the Pattern

Recognizing ground-shifting helps us navigate these conversations more productively. When someone shifts from substantive discussion to moral accusation, you can acknowledge the shift: "That's an interesting point about representation values, but I was actually asking about adaptation philosophy." Or follow them to the new ground if it's worth exploring: "Let's talk about racial representation—but first, can we agree that loving Black characters while having concerns about Superman casting suggests something more complex than simple racism?"

The goal isn't to win arguments, but to win them cleanly and decisively, without it turning ugly. When we notice grounds being shifted, we can choose whether to follow or to gently guide the conversation back to terrain where real understanding might actually grow.

Master this pattern, and you'll hold a powerful rhetorical tool. When facing uncomfortable questions, you can deftly shift grounds to more favorable terrain. But more importantly, when others attempt this maneuver on you, you'll recognize it immediately and can choose whether to follow them into their preferred domain or guide the conversation back to your original inquiry.

Keep your eyes open. You'll spot ground-shifting everywhere... from heated Instagram comment threads to boardroom discussions, from family dinner debates to cable news panels. Once you see it, you can't unsee it. And that awareness transforms you from a passive participant in conversations to an active architect of meaningful discourse.

Until next time,

The Rhetorician