First things first... I'm considering moving fully to Substack. The aesthetics seem better. What are your thoughts? Write back to me and let me know.

Now read on!

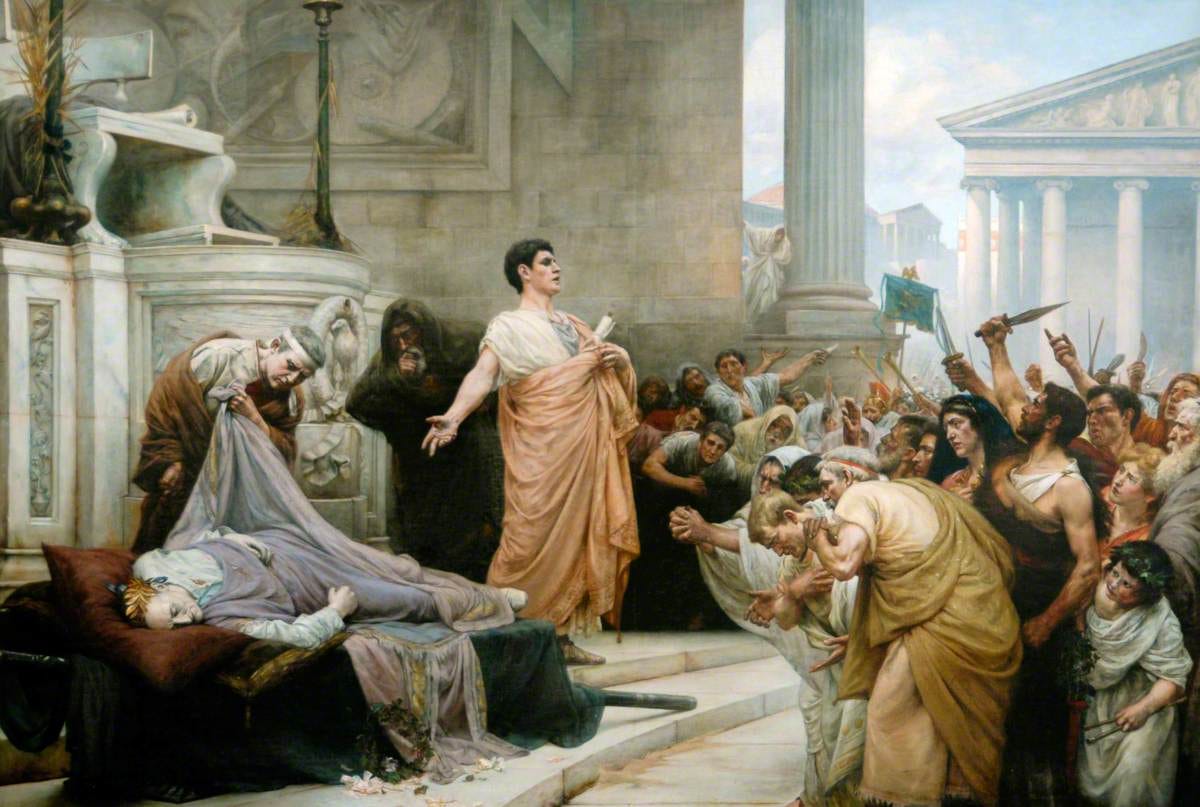

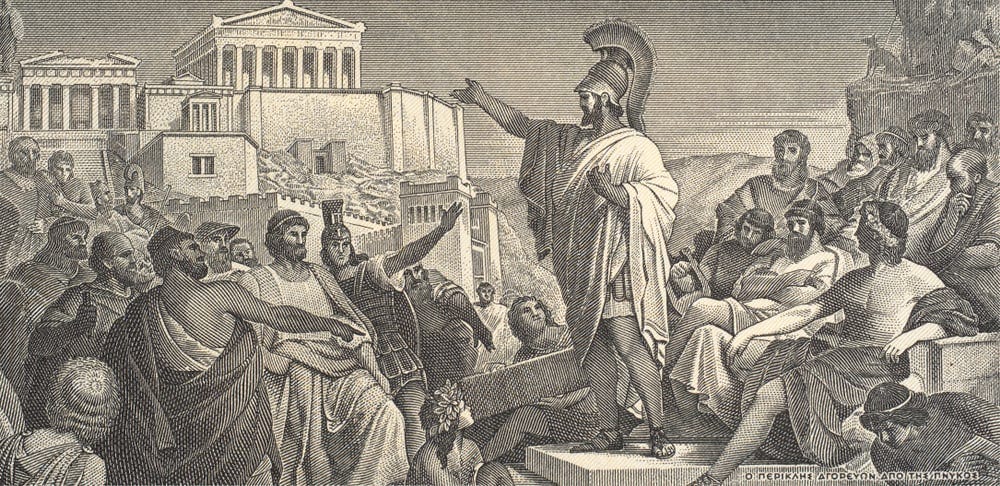

Imagine standing in the Athenian agora, 5th century BC. A crowd gathers as Pericles rises to speak. No microphone, no teleprompter—just the power of carefully chosen words, rhythmic cadence, and the ability to move hearts and minds. This was rhetoric at its zenith: the art that could start wars, forge peace, and determine the fate of nations.

But rhetoric was far more than a tool for political theater. For over two millennia, it was the very foundation of Western education, the bridge between thought and action, the means by which civilization transmitted its highest ideals.

So what happened to it? And what did we lose when rhetoric faded from the center of our cultural life?

The Ancient Foundation: When Words Built Democracies

In ancient Greece and Rome, rhetoric wasn’t merely an academic subject—it was the essential skill of citizenship itself.

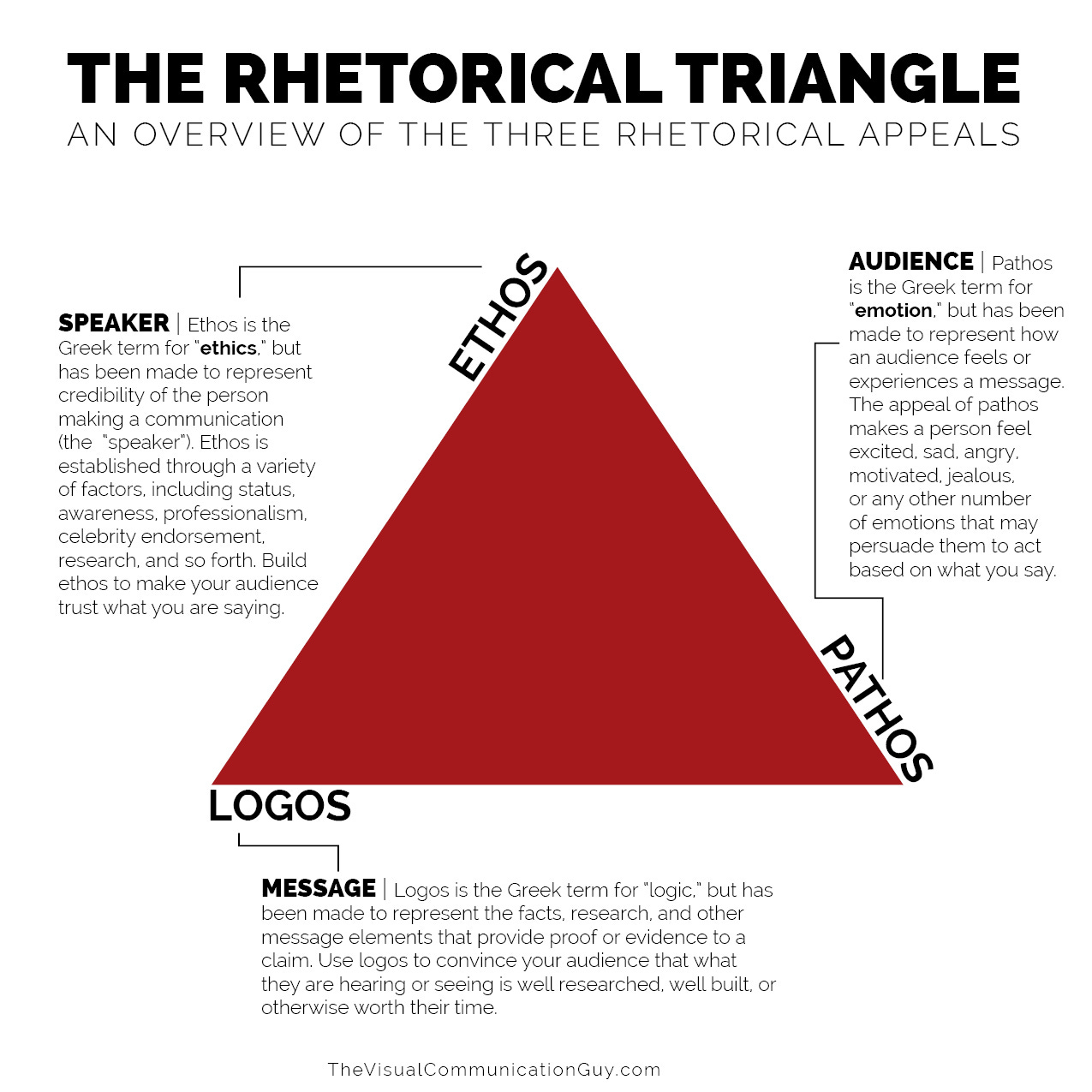

The Greeks called it rhetorike techne, the art of persuasion. Aristotle systematized it, dividing rhetoric into three modes: ethos (credibility), pathos (emotion), and logos (logic). But even before Aristotle, the Sophists recognized a profound truth: in a democracy, the person who speaks well holds power. Not the power of the sword, but something more lasting—the power to shape collective truth.

The Romans elevated this further. Cicero, the great orator-philosopher, declared that eloquence was the highest expression of wisdom joined with virtue. In the Roman Republic, a well-crafted speech in the Senate could alter the course of history. Young Romans spent years mastering the five canons of rhetoric: invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery. To speak beautifully was to think clearly, and to think clearly was to live nobly.

Rhetoric, in this classical vision, was inseparable from ethics. The perfect orator, according to Quintilian, was vir bonus dicendi peritus—”a good man skilled in speaking.” Character and eloquence were two sides of the same coin.

The Christian Transformation: Sacred Eloquence

When Constantine’s conversion brought Christianity to the throne of empire, rhetoric faced a crisis of identity. Could the pagan art of persuasion serve the Christian God?

Saint Augustine answered with a resounding yes—but with a crucial transformation. In De Doctrina Christiana (On Christian Teaching), Augustine argued that since truth came from God, Christians had both the right and duty to use every tool of eloquence to proclaim it. Why should falsehood have all the beautiful words?

But Augustine’s rhetoric served a different master than Cicero’s. The goal was no longer civic glory or political victory—it was the salvation of souls. Rhetoric became the handmaiden of theology, its purpose not to win arguments but to illuminate divine truth and move hearts toward God.

This shift had profound consequences. Rhetoric was preserved, yes, but redirected. The public square gave way to the pulpit. Civic deliberation transformed into spiritual exhortation.

The Medieval Contraction: Rhetoric in the Cloister

As the Roman Empire crumbled and barbarian kingdoms rose from its ruins, the grand tradition of classical rhetoric nearly disappeared. The forums fell silent; literacy plummeted. Who needed the art of public speaking when public life itself had collapsed?

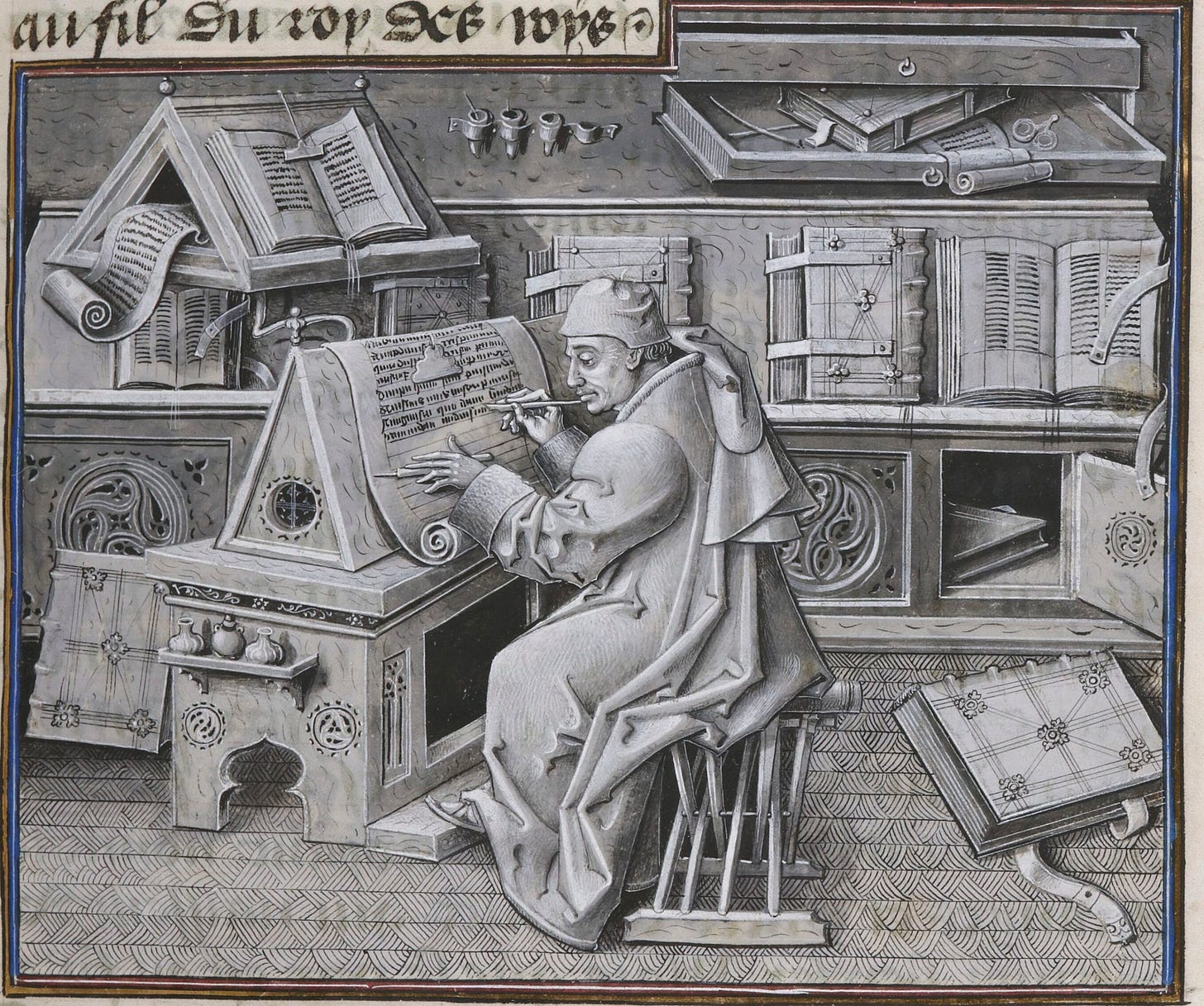

Rhetoric survived, but barely—sheltered within monastery walls as one part of the trivium, the three-fold path of medieval education: grammar, logic, and rhetoric. Young monks learned just enough eloquence to compose letters and understand scripture. The fire that once animated the Senate had been reduced to embers, carefully tended by scribes who copied ancient texts they could barely understand.

Rhetoric became a clerical tool, stripped of its civic grandeur. The art that once belonged to every citizen was now the possession of a learned elite, used primarily for administrative correspondence and biblical interpretation.

The Scholastic Refinement: Specialized Arts

The High Middle Ages brought a renaissance of learning, but not quite a renaissance of classical rhetoric. Instead, medieval scholars did what they did best: they systematized, categorized, and specialized.

Two new arts emerged, both descendants of classical rhetoric but adapted to medieval needs:

Ars dictaminis—the art of letter-writing—became essential for papal bureaucracy, royal chancelleries, and commercial correspondence. Elaborate rules governed how to address a bishop versus a king, how to structure a petition, how to conclude a diplomatic missive. It was rhetoric, but rhetoric reduced to formula.

Ars praedicandi—the art of preaching—offered guidelines for composing sermons. How to open with scripture, how to divide your points, how to apply moral lessons. Again, rhetoric survived, but in the service of the Church rather than the state.

Meanwhile, dialectic (logic) ascended to dominance in the universities. The subtle arguments of Thomas Aquinas and other schoolmen prized precision over beauty, demonstration over persuasion. Rhetoric found itself subordinated, no longer queen of the arts but a useful servant.

The Italian Awakening: Eloquence Returns to the Square

Then something remarkable happened in the Italian city-states of the 14th century.

As communes like Florence, Venice, and Milan grew wealthy through trade, they required skilled administrators—chancellors, secretaries, ambassadors who could compose compelling letters, negotiate treaties, and represent their cities with dignity. The old clerical rhetoric wasn’t enough. These urban republics needed something closer to the ancient ideal: eloquent citizens who could deliberate, persuade, and defend their freedoms.

Enter the humanists. Petrarch had already begun the work in the 1300s, dusting off forgotten manuscripts of Cicero and lamenting the “barbarous” Latin of his scholastic contemporaries. But it was the 15th century that witnessed the true revival.

Humanist educators realized that to restore eloquence, you had to restore the classical texts themselves. They hunted through monastery libraries for lost works of Quintilian and Cicero. They studied not just what the ancients said, but how they said it—their rhythms, their metaphors, their very breath.

The Florentine Peak: Virtue and Eloquence United

By the late 15th century, Lorenzo de’ Medici’s Florence had become the epicenter of this rhetorical renaissance.

The Platonic Academy—founded by Lorenzo’s grandfather Cosimo and led by Marsilio Ficino—had been nurturing this revival for decades. Ficino himself had tutored the young Lorenzo, instilling in him a reverence for eloquence wedded to wisdom. Under Lorenzo’s rule, this circle expanded to include brilliant minds like Pico della Mirandola, all dedicated to fusing classical learning with Christian truth. Unlike the medieval schoolmen who valued logic above all, these humanists believed that eloquence itself was a form of wisdom—perhaps the highest form.

Why? Because rhetoric, properly understood, united thought and action, wisdom and virtue, the individual soul and the common good.

In Lorenzo’s Florence, rhetoric regained its civic prestige. Young patricians learned to speak beautifully not merely to impress, but to serve the republic. The ideal was Cicero’s vision reborn: the cultivated citizen whose eloquence flowed from moral character, whose words could elevate public life.

This was rhetoric at its Renaissance peak—no longer confined to clerics or reduced to technical manuals, but restored to its ancient dignity as the art that made civilization possible.

The Long Reign—and the Great Forgetting

For centuries after Lorenzo’s Florence, rhetoric remained the cornerstone of Western education. Through the Enlightenment, into the Victorian age, every educated person studied the art of eloquent expression. To be cultured meant to speak and write with clarity, grace, and power. Universities structured their curricula around it. Statesmen were measured by it. The ability to articulate thought beautifully was inseparable from the ability to think profoundly.

But something shifted in the 20th century.

As technical specialization accelerated and efficiency became the supreme value, rhetoric was quietly pushed aside. Universities replaced eloquence with expertise, communication skills with career preparation. The liberal arts—once the training ground for free citizens—gave way to narrow vocational training. We learned to code, to engineer, to optimize, but we stopped learning to speak from the soul.

The consequences have been more devastating than we realized.

The Cost of Inarticulacy

When you lose the art of eloquent expression, you don’t just lose the ability to persuade others. You lose something far more essential: the ability to know yourself.

Rhetoric was never merely about external persuasion—it was a tool for internal clarity. The discipline of shaping thought into language, of finding the precise words for inchoate feelings, of articulating what you truly desire—this is how humans come to understand their own hearts. Without it, we become strangers to ourselves.

Look around at our contemporary condition: a technically competent civilization that cannot name what it hungers for. We have material abundance yet spiritual poverty. We scroll endlessly, consume frantically, chase experience after experience, because we lack the language to identify the deeper longing. We’re constantly seeking meaning but remain unable to articulate what meaning would even look like.

We built a world of unprecedented comfort and possibility—and filled it with people who can’t explain what they actually want from life.

This is what happens when eloquence dies. We don’t just lose beautiful speeches or elegant prose. We lose access to our own interiority. We become, in the deepest sense, inarticulate—not just to others, but to ourselves.

The AI Reckoning: Why Eloquence Matters Now More Than Ever

And now we stand at another threshold, perhaps the most crucial one yet.

We’ve entered an age where our words don’t just describe reality—they create it. Every prompt we write, every query we make, every instruction we give to artificial intelligence becomes an act of world-building. The machines don’t just respond to our commands; they amplify our clarity or multiply our confusion.

If you can’t articulate what you truly want, if you lack the precision to express your deepest values, if your language is clumsy and vague—the tools you wield will produce exactly that: clumsy, vague, soulless output. Technical competence without eloquent expression doesn’t give you mastery over these new tools. It makes you their servant.

This is why the revival of rhetoric isn’t just nostalgic—it’s existential.

In an age of artificial intelligence, the ability to express yourself with clarity, depth, and beauty isn’t a luxury. It’s the difference between shaping the future and being shaped by it. Between directing powerful tools toward human flourishing and watching them amplify our worst confusions. Between preserving what remains of our souls and surrendering completely to efficient emptiness.

The humanists understood something we’ve forgotten: eloquence is intelligence made visible. It’s the bridge between inner wisdom and outer action. It’s how we clarify our values, articulate our vision, and pass on what matters most to the next generation.

What We Inherited—and What We Must Reclaim

The rhetorical tradition that began in Athens and reached its Renaissance flowering gave us more than techniques for persuasion. It gave us a model of education centered on human excellence, a vision of citizenship grounded in eloquent participation, and the belief that beauty of expression reflected beauty of soul.

When we study the journey of rhetoric—from the agora to the cloister, from scholastic specialization to humanist revival, and finally to its 20th-century eclipse—we’re really studying the story of Western culture itself. We’re watching civilization struggle to preserve what matters most, sometimes losing it nearly completely, then rediscovering it when the need becomes urgent.

That need has never been more urgent than now.

We stand at a crossroads. One path leads deeper into technical mastery without wisdom, efficiency without soul, power without purpose. The other leads back to an ancient truth: that how we speak shapes how we think, how we think determines how we live, and how we live decides what kind of world we create.

Perhaps, like the humanists who rediscovered Cicero in forgotten libraries, we need to ask ourselves what we’ve lost. The art of knowing ourselves through articulate expression. The discipline of clarifying desire through eloquent speech. The capacity to pass on meaning through beautiful language.

And whether it’s time to bring eloquence home again—not as a relic of the past, but as a living art for a civilization that desperately needs to remember how to speak from the soul, especially now, when our words have the power to shape reality itself.

Thanks for reading The Rhetorician! Share it with someone who’s fascinated with Western History!

The greatest orators of history understood something we’re still learning: that how we speak shapes how we think, and how we think determines how we live. Rhetoric isn’t just about winning arguments—it’s about building the kind of culture worthy of beautiful speech.