How to Arrange Your Ideas for Maximum Persuasion

|

The Rhetorician

Join 100+ readers in learning the Art of Rhetoric: Timeless Techniques of Persuasion that helped history's giants navigate courtroom politics, win wars, and build civilisations.

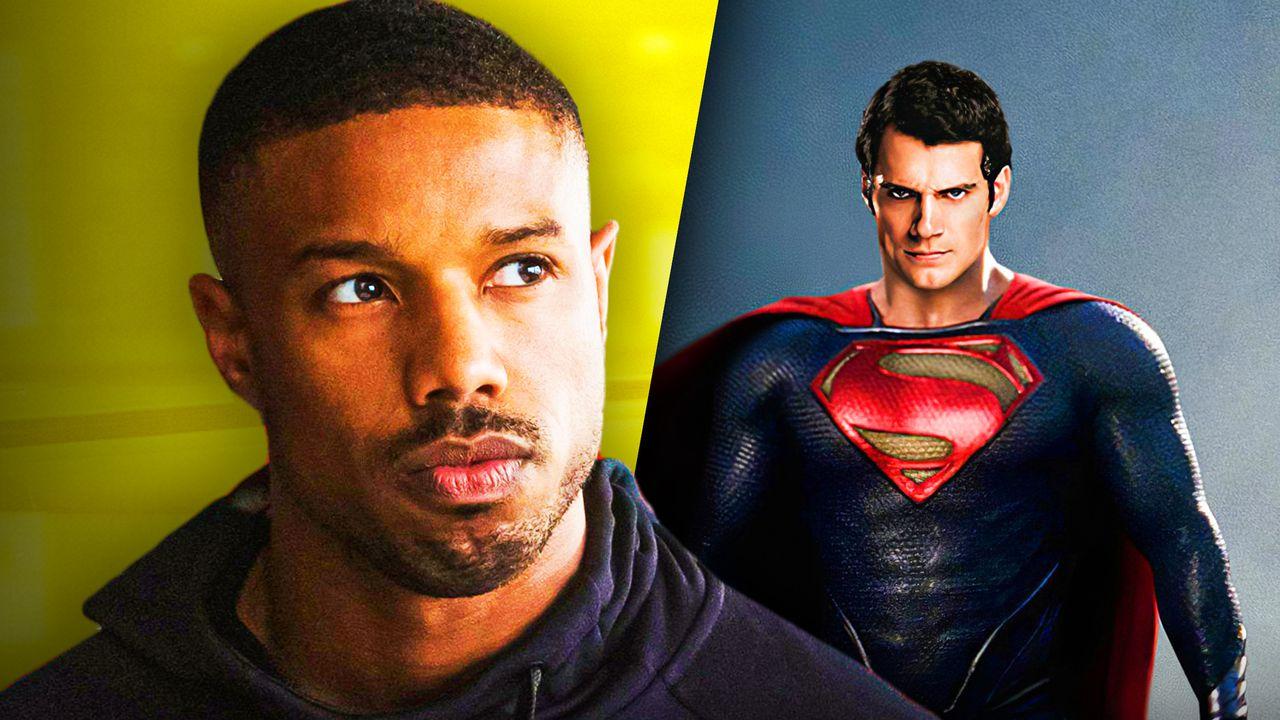

The Rhetorician Issue #15 Black Superman: The Art of Shifting Grounds to Win Arguments img src: https://thedirect.com/article/michael-b-jordan-black-superman-casting-rumors Occasionally, reports surface of a Black actor being cast as Superman—and the internet predictably erupts. Twitter wars rage, comment sections become battlefields, and everyone picks a side. But buried beneath this familiar cultural skirmish lies a fascinating example of a rhetorical maneuver that shapes far more of our...

The Rhetorician Issue #15 From Confrontation to Collaboration: Making Discussions Productive with the Strategic Concession Technique Dear Readers, We've all encountered people with whom productive discussions seem nearly impossible. They tend to take every counterpoint as a personal attack, becoming so defensive that they practically close themselves off to any new input. The curious thing is that they often don't see themselves this way at all - in their minds, they're simply being thorough...

The Rhetorician Issue #14 Rhetorical Analysis: Thomas Shelby Dear readers, Today I'm here with a rhetorical analysis of one of the better speeches in pop culture in recent times - Thomas Shelby's speech in parliament in the beginning of Season 5. Peaky Blinders' writing has been first rate since the show's inception, and there's a lot that we, the rhetoricians, have to learn from it. In this analysis you will be able to see (and hopefully recognize) some of the concepts we've talked about...